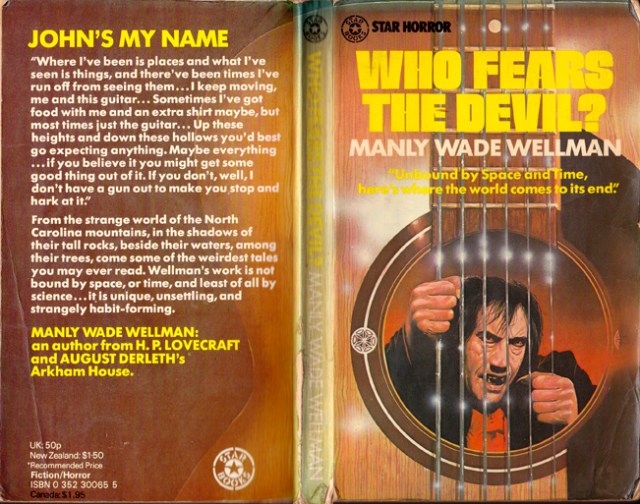

It’s easy to dismiss these celebrity linked anthologies as populist tat cashing in on a star turn to shift a few units, but it would be a shame to overlook them as this one’s a corker and worth the cover price just for Christopher Lee’s introduction alone.

Lee tells us that he (probably more than ably assisted by Michel Parry, a famed horror anthologist himself) chose the stories in this collection as they all have “…the personal appeal of reminding me of some aspect or another of my career as an actor.”

What follows in his introduction is the most brilliant series of name-drops you’re likely to read and best read with Lee’s sonorous tones in mind:

Take for instance, The Spider by Fritz Lieber, an author I had the pleasure of meeting in Hollywood.

Or…

…The Man with the Golden Gun in which I played Scaramanga. The creator of 007 was, of course, the late Ian Fleming and one of the stories which I have selected was written by Ian’s brother, Peter. Incidentally, it is not generally known that I was distantly related to both Ian and Peter, they were my step-cousins.

Or…

Curiously enough, I once actually met Conrad Veidt when I was a young boy. Apparently he was a keen golfer (like me) and I was introduced to him on a golf-course back in 1938 or 1939.

C O N T E N TS

Introduction – Christopher Lee

The Spider – Fritz Leiber

I, The Vampire – Henry Kuttner

Talent – Robert Bloch

Amber Print – Basil Copper

The Gorgon – Clark Ashton Smith

The Kill – Peter Fleming

Blood Son – Richard Matheson

The Black Stone – Robert E. Howard

The Monster-Maker – W. C. Morrow

The Judge’s House – Bram Stoker

The Spider – Fritz Leiber

This story, which is possibly a comment against the juvenilisation of the genre, begins with a trio of people on a city street on a winter’s night. We do not know who they are, Leiber enigmatically refers to them as The Beautiful People. We have The Old Man with a hawk like face, grey hair and a black overcoat with an astrakhan collar; The Other Man with his collar pulled up, his brimmed hat pulled down, dark glasses, thick gloves and a strange accent; The Woman has a ‘slim queenliness’ in her black evening gown and velvet cloak.

Lee suggests in his introduction that these three are Dracula, The Invisible Man and The Bride of Frankenstein but I see no real evidence for this. They certainly represent the classic anti-heroes of horror fiction but I think Leiber is too classy a writer to sully his work, by specifying these characters he would risk reducing them to two dimensional clichés.

The reason these three are hanging about on a street corner is the unlikely named Gibby Monzer. Gibby is a cynic, a skeptic, a believer in science. He makes his money from producing comic strips mocking the characters from classic horror, portraying them as “louts, lugs, zanies, morons and stumblebums”. The Beautiful People have decided to pay Gibby a visit, or rather they decide to send an emissary, while he relaxes in his apartment.

I, The Vampire – Henry Kuttner

Kuttner was part of the Weird Tales set in the 30s and 40s and also involved with the “Lovecraft Circle”, along with his wife and fellow genre author C.L. Moore (with whom he co-wrote many stories under the shared pen-name of Lewis Padgett). Incredibly influential, he is cited as an inspiration to many later greats, including Ray Bradbury and Richard Matheson (Matheson even dedicated I Am Legend to him).

Written in 1937, this is one of his earlier tales, the story of a Vampire in modern day Hollywood. It’s also an early example of what has become a staple of the genre, the ‘sympathetic’ vampire. Here, Kuttner takes the glitz and glamour of the film studios of 1930s Hollywood and deftly transforms them into the setting for a classic gothic tragedy.

“I went out on the porch and leaned against a pillar, sipping a cocktail and looking down at the lights of Hollywood. Hardy’s place was on the summit of a hill overlooking the film capital, near Falcon Lair, Valentino’s famous turreted castle. I shivered a little. Fog was sweeping in from Santa Monica, blotting out the lights to the west.”

Talent – Robert Bloch

Robert Bloch is probably best known as the author the novel Psycho, on which Hitchcock based the film of the same name. Another exceptionally prolific author writing countless novels, short stories and screenplays (many of the wonderful Amicus portmanteau films of the ‘60s and ‘70s were adapted by him from his own stories). This is a typically darkly humorous piece from Bloch written in a reportage style about a foundling child who discovers a talent for imitation after the orphanage decide to hold a weekly film night. It all starts innocently enough with a Marx brothers film, but as the child discovers more and more genre films the story takes a turn towards the sinister.

Amber Print – Basil Copper

There’s a hint of Richard Marsh’s Victorian series of classic short stories ‘Curios’ about Copper’s contribution, in that it concerns a pair of mildly eccentric bachelor collectors. But whereas Marsh’s duo collect a variety of esoteric antiquities, Copper’s pair of bachelors hold more select collections. Mr Carter and Mr Blenkinsop collect rare film reels. In this tale Mr. Blenkinsop acquires an exceptionally rare and previously unheard of print of Robert Weine’s legendary 1920 film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. The pair’s initial excitement soon wears off when they discover that the protagonists of the film, Caligari and Cesare, do not necessarily seem content to stay on the screen. Copper writes this story with an obvious love for the film and makes for a fitting homage.

The Gorgon – Clark Ashton Smith

I was quite excited to read on the acknowledgements page that this story was from 1923 which would place it in Smith’s early poetic phase. However, it reads like a much later piece and, with a little research, I found that it’s actually from 1932, which makes much more sense. Smith was another, and arguably the most influential, member of the Lovecraft circle and, being written in that wonderfully typical verbose style, The Gorgon bears testament to this. Rather than being set in one of Smith’s ‘fantastic’ lands this tale unfolds in the foggy streets of contemporary London…well, mostly! Being a Clark Ashton Smith story we’re in a dreamlike, hallucinatory state where time and place have little meaning, words like ‘where’ and ‘when’ do not refer to the fundamental truths we’re used to, they tend to bend and morph into one another.

The Kill – Peter Fleming

This is an interesting one. I first encountered it in the first Pan Book of Horror Stories and I’ve never forgotten it. The introduction is well observed with a beautiful and cynically cold writing style (which, to give a more contemporary reference point, is reminiscent of Will Self’s style). It seems to be setting up a perfect short story which could be, to give another reference, quite Chekhovian in that it’s a theatrical, single scene, one act, two-hander. However, it devolves into a story within a story which one of the two characters narrates to the other and this secondary tale takes precedence. I can’t help feeling that Fleming missed a trick in not developing the initial setting to run alongside the secondary but he chose the linear method of introduction – narration – denouement, but he was a young writer at the beginning of his career at the time so perhaps we can forgive him that. It’s such a shame that Peter Fleming (older brother of Ian) was such an explorer and adventurer and dedicated most of his time to travel writing rather than developing his skills with fiction. Anyway, here’s the corker of opening scene-setter:

Blood Son – Richard Matheson

In the introduction to this story Lee suggests Matheson is “…without any doubt, one of the greatest writers in this marvellous field of fantasy and the macabre and grotesque”. He’s right about that. Sadly, Matheson died last year but left behind him a legacy of novels, short stories and screenplays. In Blood Son, Matheson gives us a fresh twist on the vampire story (as he did with I am Legend, probably his most famous novel). It concerns a disturbed boy, Jules, who from birth had a vacuous stare and was silent. He didn’t speak until he was five years old when his first word was “death”. From that point Jules started to develop a large vocabulary, the young neologist enjoyed creating portmanteau words such as “…nightouch” and “…killove”. And at the age of twelve when Jules sees the film version of Dracula and subsequently reads the Stoker novel (again and again and again) he becomes obsessed with idea of becoming a vampire, much to the concern of everyone around him.

The Black Stone – Robert E. Howard

Being the author of the Conan series, among others, Robert E. Howard was better known as a progenitor of the Sword & Sorcery genre. For such a short life (he committed suicide at the age of thirty) he was remarkably prolific. He held a long time epistolary relationship with H.P. Lovecraft and is considered yet another member of the Lovecraft circle; this influence can be seen in The Black Stone, being a first person narration concerning an investigation into an ancient monolith which stands in a pine forest on a Hungarian mountainside and the Midsummer pagan rites witnessed there. Howard introduces us to a new tome of Yogsothery, Nameless Cults by Friedrich Wilhelm von Junzt. He also alludes to a mad poet by the name of Justin Geoffrey.

The Monster Maker – W.C. Morrow

Morrow offers us a tale of a surgeon who has a sideline in assisting young men to end their lives. They visit him in his large, dilapidated and dismal house in an unfashionable part of town and, at their request, he dispatches them quickly, cleanly and quietly. Or does he? If he does then why does the surgeon’s wife wonder why he always insists on eating in his private room? And why does he take more food than any one man could possible eat?……….and they say torture porn is a modern invention!

The Judge’s House – Bram Stoker

This a much anthologised story, it’s Bram Stoker…of course it’s much anthologised! If it wasn’t this one then it would have been The Squaw or Dracula’s Guest. As you would expect, it’s a wonderfully atmospheric piece in that late Victorian / Edwardian dark gothic kind of a way. It concerns a young scholar who decides to get away from it all to study for his upcoming examinations. He rents a dishevelled Jacobean manor house which has stood empty and rat-infested since the last owner, an infamous judge known for the number of death-sentences he pronounced, died. As is so often the case in these tales of the supernatural, even the logical mind of a young and cynical scholar can easily be overwhelmed by dark forces, especially when the aforementioned scholar discovers that the bell rope in the living room was custom made for the judge from the rope his executioner used to hang his victims.