“Horse and hattock, horse and go,

Isobel Gowdie ~ Flying Incantation

‘Horse and pellatis, ho! ho!”

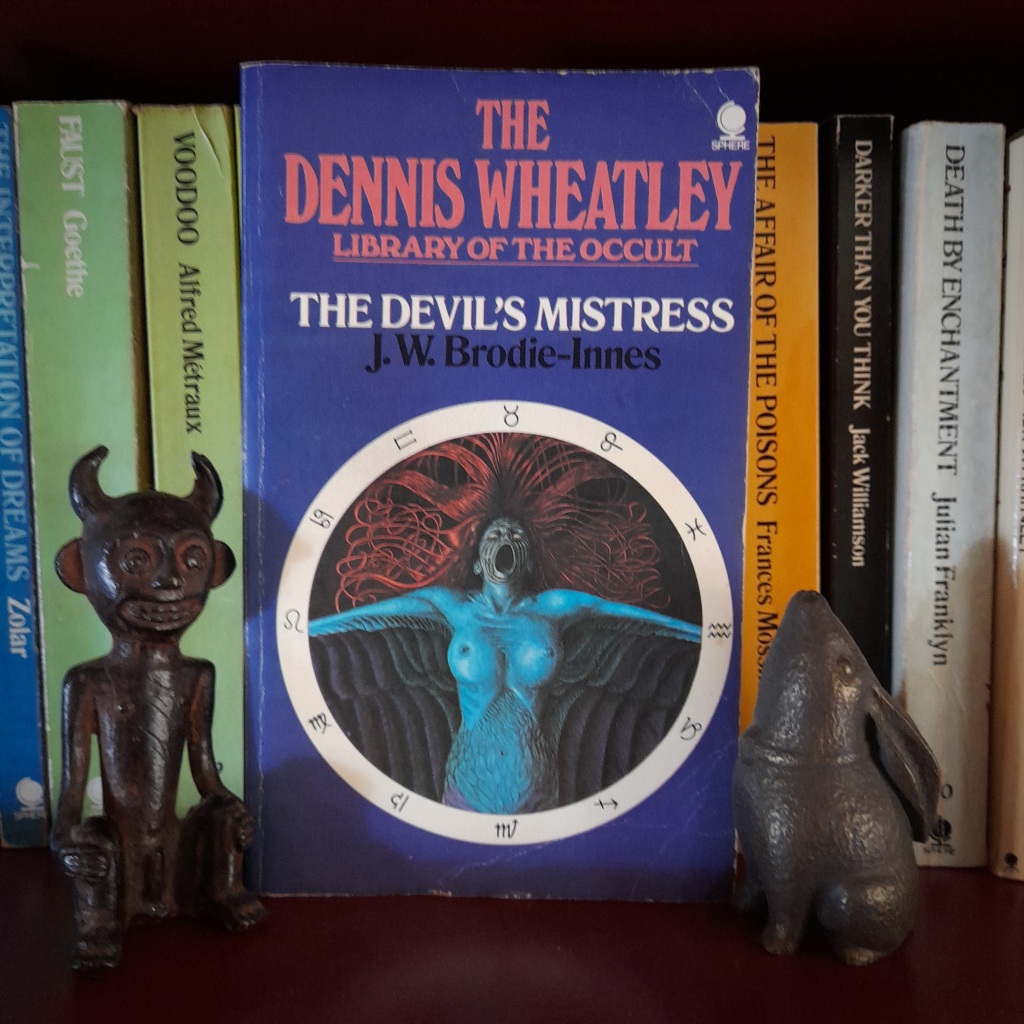

Volume 11 of The Dennis Wheatley Library of the Occult offers us this tale of 17th Century witchcraft set in the Scottish Highlands. Originally published in 1915, this is a fictionalised tale of the true account of the testimonials of Isobel Gowdie, of course these testimonials may indeed have been fictionalised by Gowdie herself in the first place; so we have multiple layers of fiction and truth to pick through.

To tell the tale of Isobel Gowdie and how this novel came about I’m going to have to peel back some of the drier layers so that we can feast on the juicier bits at the end. So, here we go… let’s introduce J. W Brodie-Innes first of all.

J. W. Brodie Innes (1848 -1923)

Brodie-Innes was a well-known occultist in his day, being a member of Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society and, later, a high-ranking member of The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. A lawyer by profession; he also wrote a handful of novels (all historical romances with folklore/occult themes) and various articles on the occult which appeared in journals such as ‘Lucifer’ and ‘The Occult Review’.

As I mentioned, The Devil’s Mistress was first published in 1915, but let us first go back a couple of decades. Along with being a member of the occult societies already mentioned, Brodie-Innes was also a member of a rather eccentric society of bibliophiles called The Sette of Odd Volumes. The members of this peculiar group published their own limited print volumes on a variety of subjects from collecting Blue and White China to the work of the 16th Century physician, Gilbert of Colchester. Amongst these volumes we can find one by our J. W. Brodie-Innes which has the title of ‘Scottish Witchcraft Trials’.

This small volume was published in 1890 (25 years before The Devil’s Mistress) and is a brief discourse on, as the title suggests, the various witch trials which occurred in Scotland in the 16th and 17th centuries. In this book, Brodie-Innes gives us a brief mention of the remarkable confessions of Isobel Gowdie. Should you be interested, you can read the whole of Brodie-Innes’ volume here:

https://archive.org/details/b24866453/mode/2up

So, where did Brodie-Innes get all this information about the Scottish witch trials? Well, we’ll have to go back a little further in time for that and meet Robert Pitcairn.

Robert Pitcairn (1793-1855)

Pitcairn was a Scottish antiquary. Like Brodie-Innes, he was a lawyer by profession and, like Brodie-Innes, he was a member of a literary society; whereas Brodie-Innes was a member of The Sette of Odd Volumes, Pitcairn was a member of a society led by Sir Walter Scott called The Bannatyne Club. In 1833 Pitcairn published a three volume set for The Bannatyne Club with the title of ‘Ancient Criminal Trials in Scotland’. In this publication Pitcairn diligently compiled the transcriptions of a number of Scottish trials from the 16th and 17th centuries; amongst these trials were, of course, a number of trials for witchcraft. If we flick through the pages of ‘Ancient Criminal Trials in Scotland’ and get towards the end of the third volume, in the appendices, on page 602, we will find the first of four confessions of Isobel Gowdie.

Gowdie’s confessions are considered to be one of the most remarkable confessions to arise from a witch-trial and, perhaps more remarkable, they are said to have been offered without torture. You can read the whole of the four testimonials beginning on page 602 here:

https://digital.nls.uk/publications-by-scottish-clubs/archive/78739514

Although Pitcairn was the first to publish the testimonials he wasn’t the first to mention Isobel Gowdie in print. This honour goes to none other than Sir Walter Scott himself, this was in his 1830 publication with the title of ‘Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft’. In this volume Scott references the Gowdie trial a number of times and we can imagine that Pitcairn perhaps helped him with this.

So, what of Isobel Gowdie herself?

Much has been written about Isobel Gowdie over the last 200 years; her story has spawned a handful of novels, various musical interpretations and inspired countless books on witchcraft; yet we know very little about her. All the details we know of her come solely from her trial. We know she was a woman of indeterminate age who lived at Lochloy with her husband John Gilbert, a farm worker.

However, we also know that she gave such an extraordinary and detailed testimonial that she, perhaps inadvertently, changed the occult landscape of the 20th century. As one small example, we all know that a group of witches is called a coven and, in most traditions, a coven consists of thirteen members… this information comes directly from Gowdie’s trial, it just doesn’t seem to exist prior to that. How did this information spread so quickly? Well we’ve have to introduce Margaret Murray for this.

Margaret Murray (1863-1963)

As you probably know, Margaret Murray was a folklorist and archaeologist and in 1921 published her influential book, The Witch-Cult in Western Europe. This book was an expansion of her earlier article published in The Folklore Society journal in 1917. In this, Murray suggested that ‘witches’ were followers of an organised, pre-Christian religion which survived until the 17th century. Within this religion the practitioners were divided into covens, each coven having thirteen members, and they worshipped a pre-Christian horned god which, in a Christianised world, became the devil. Much of Murray’s research for this theory seems to have been derived from Pitcairn’s publication and she pays particular attention to the Isobel Gowdie case.

Margaret Murray’s The Witch-Cult in Western Europe can be read here:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/20411/20411-h/20411-h.htm

Perhaps we should return to the novel in question for a bit now.

The Devil’s Mistress

I believe Brodie-Innes was the first to fictionalise the accounts of Isobel Gowdie. As we would perhaps expect from a Victorian occultist, Brodie-Innes presents the novel as though Gowdie’s testimonials were a true account of her activities. The story picks up on most of the details of Gowdie’s claims, beginning with her first meeting with the ‘Dark Master’, her induction into the coven and subsequent magical acts. Of course, as the original transcript has so little detail about Gowdie’s life outside of her magical acts, Brodie-Innes fleshes it out for us. Isobel Gowdie is not just a poor farmer’s wife, she becomes the well-educated daughter of a country lawyer who was sold into a marriage to the dour and gloomy farmer to pay off a debt. And in true romantic heroine style she is a flame-haired beauty too:

“she was strangely unlike the women of the farmer class in the province of Moray, being tall and slight, with a mass of flaming red hair, deep brown eyes that seemed as though brooding over hidden fires, dark eyebrows almost straight in a face that seemed unnaturally pale, a slightly arched nose, and full red lips.”

Brodie-Innes has a tendency to slip into these awful, sentimental, romantic-fiction stylings on occasion but, thankfully, they do tend to peter out a bit as the book progresses. As we would expect, the novel explores Gowdie’s relationship with ‘The Dark Master’ and the rest of the coven, with characters taken directly from the testimonials; it also takes other real life characters from the locality and the period and fits them in with the narrative. One of these characters is Sir Robert Gordon, or The Wizard of Gordonstoun, who was reputed to be an alchemist/occultist who had sold his soul to the devil. Although Brodie-Innes has got his time-lines a little awry with the inclusion Gordon as a friend to Gowdie, I’m happy to forgive him this as it makes for an exciting storyline.

Although this novel is a much romanticised version of events, I think it is an important work of occult fiction. Brodie-Innes deals with the various magical acts in a sensitive and subtle way, leaving a little ambiguity about them; often, Gowdie herself is not sure whether she was actually away performing magical rites with the coven or whether she was safely in her bed and dreaming that she was doing this. Yet still the results of those magical rites come about. This is perhaps exemplified best when Isobel asks her fellow coven member, Margaret Brodie, about whether she is dreaming these things or whether they are real, and she answers:

‘I’ve often wondered,’ Margaret answered after a pause while she seemed to be thinking what to say. ‘We do queer things sometimes. For instance, ye know Maggie Wilson in Aulderne. Well, she has her old man to consider. But she comes with us when we are out for revelling. She just puts a besom in the bed, and the old man thinks it is herself, and never misses her. But whether it is her that’s at home, or her that’s with us, none knows, or whether she is two women on that night. And she doesn’t know. She swears she is with us, and the old man says she is at home. Well, ye ken whiles I have thought it may be the same with the Dark Master. Perhaps he is just a man who has learned many things, and makes us think he is the Devil, as Maggie makes her man think that the besom is her. Or he may indeed be the Devil and makes us think whiles that he is just a man. Or perhaps he isn’t there at all, but we just fancy he is. But there, dearie, it’s no good wondering. Life is fine, and we are the queens of the country; while he helps us we can do what we will, and the country doesn’t know it. So we’ve only got to hold our tongues, lest they burn us some day, and just enjoy our time while we have it.’

In the novel, as in the original testimonials, Isobel Gowdie’s coven has thirteen members and is led by ‘The Dark Master’. Hers is just one coven amongst many and they often convene with each other, the covens not separate entities but they appear to be part of a larger whole. Which brings us back to Margaret Murray and her Witch-Cult ideas.

The Witch-Cult Hypothesis

Two years after the publication of The Devil’s Mistress, Brodie Innes had an article on witchcraft published in the May 1917 edition of The Occult Review. In this article he references Isobel Gowdie several times and, as we can see in the excerpt below, he includes the term ‘cult of the witch’.

“If we will but for a moment lay aside prejudice, and look at the subject dispassionately, we shall become convinced that the cult of the witch is as old as humanity, it is as old as the world, and as flourishing today as it was in the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries, and as firmly believed.”

Interestingly, Margaret Murray’s article ‘Organisation of Witches in Great Britain’ appeared in the April 1917 edition of the Folklore Society Journal, this is the article in which she first formulates her Witch Cult theory.

“Witch cult and ritual have not, as far as I am aware, been subject to a searching and scientific investigation from the anthropological side. The whole thing has generally been put down to hypnotism, hysteria and hallucination on the part of the witches, to prejudice and cruelty on the part of the judges. I shall try to prove that the hysteria-cum-prejudice theory, including that “blessed word” auto-suggestion is untenable, and that among the witches we have the remains of a fully organised religious cult, which at one time spread over Central and Western Europe, and of which traces are found in the present day.”

It seems that the ‘Witch-Cult’ hypothesis was really gathering pace at this time and would soon give rise to the resurgence of the pagan based occult traditions of the 20th century. It is a rather beautiful, though now widely considered flawed, theory and I don’t think it’s too much of an exaggeration to suggest that it became the basis of a large part of mid to late 20th century occult thought and the resurgence of Pagan based practices. Gowdie’s reach really was quite far reaching!.

Isobel Gowdie

We know nothing about Isobel Gowdie’s life before the confessions and we know nothing of her life after the confessions. We do not know whether she was burnt following her confessions or whether she was freed.

We do not know whether she was a witch or not, but I will say this – if spells are words spoken with intent which are intended to cause a magical change or effect, then these words spoken by Isobel Gowdie during the Spring of 1662 wove a very complex pattern, the threads of which some people are still following to this day, 360 years after they were first uttered.

Let’s leave the final words to Isobel herself:

“And the Witches yet that are untaken, have their own powers and our powers which we had before we were taken. But now I have no power at all.”

Isobel Gowdie

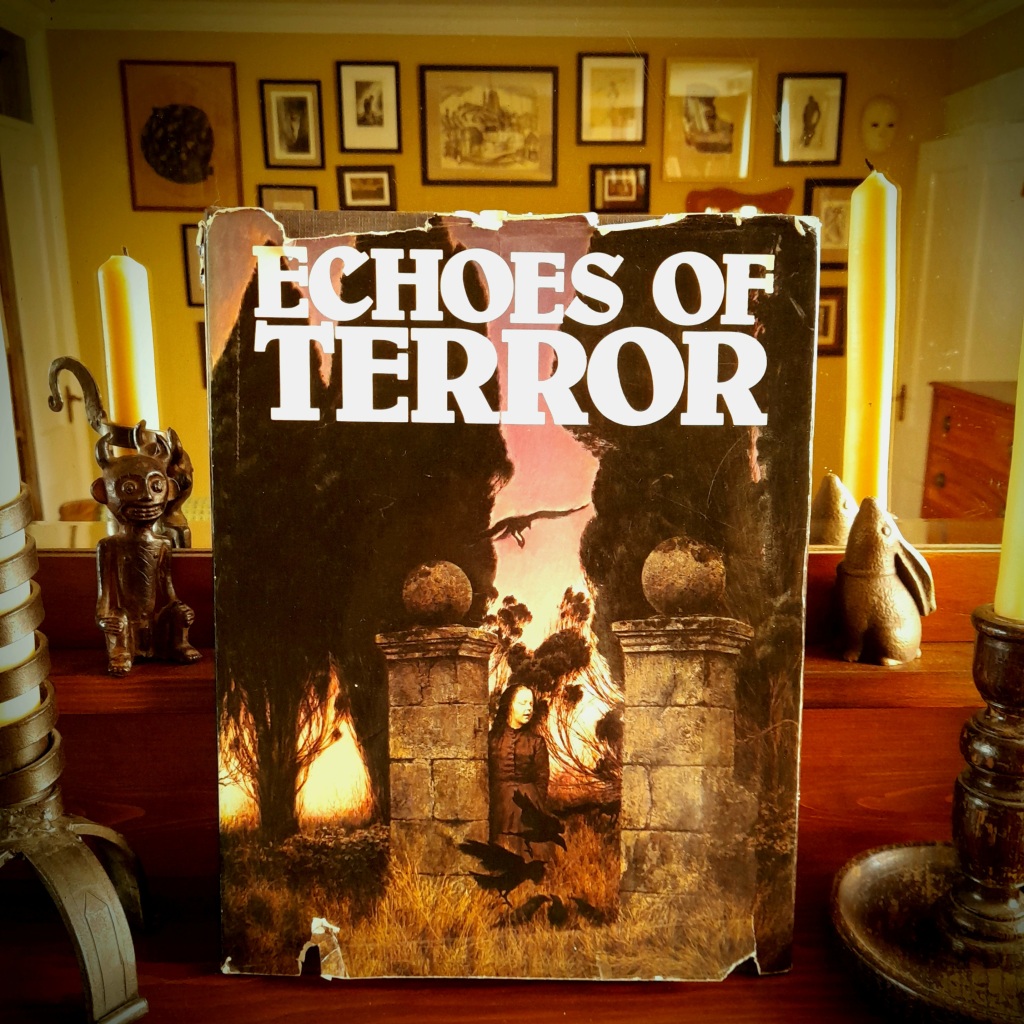

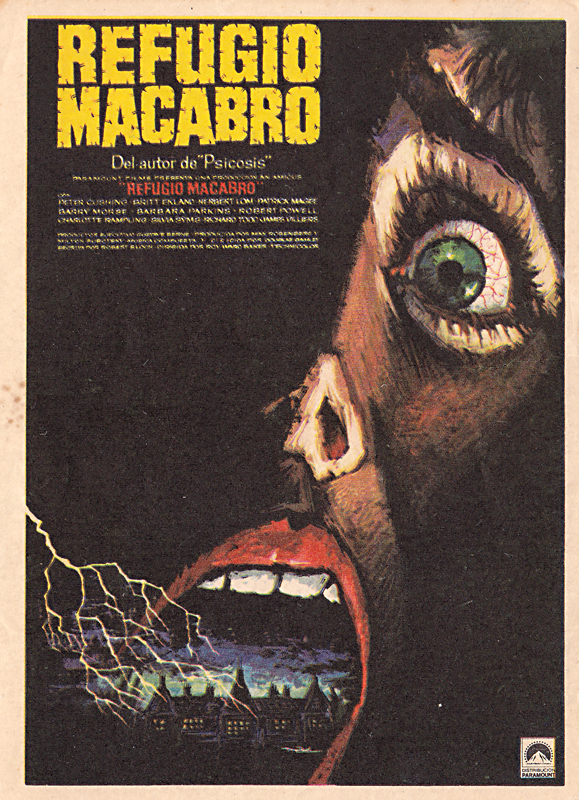

In the fourth episode, Baby, a young couple move into an old farmhouse and during renovation they discover a large urn bricked into a cavity in the wall. When they crack open the seal they discover inside the dry remains of an unidentifiable creature. This sets into motion a tale of ancient witchcraft and a familiar spirit. Interestingly, W. Walter Gill published a book concerning the history and folklore of the Isle of Man called A Manx Scrapbook; this was published in 1929, two years before Gef appeared, and in it Gill relates a tale which occurred at Doarlish Cashen:

In the fourth episode, Baby, a young couple move into an old farmhouse and during renovation they discover a large urn bricked into a cavity in the wall. When they crack open the seal they discover inside the dry remains of an unidentifiable creature. This sets into motion a tale of ancient witchcraft and a familiar spirit. Interestingly, W. Walter Gill published a book concerning the history and folklore of the Isle of Man called A Manx Scrapbook; this was published in 1929, two years before Gef appeared, and in it Gill relates a tale which occurred at Doarlish Cashen: